A Marxist Guide to Capitalist Crises

“A Marxist Guide to Capitalist Crises,” an eBook created from the key posts on the Critique of Crisis Theory blog, is currently in production. We’ll be sharing the completed chapters between our regular postings.

Chapter 22: Henryk Grossman and Long Cycles

Henryk Grossman was born to Jewish parents in 1881 in what is now Krakow, Poland. (1) The Austrian-Hungarian Empire ruled Krakow at the time. As a high school student, he became politically active and joined the Social Democratic Party of Galicia. The Social Democratic Party of Galicia was dominated by followers of Józef Piłsudski (1867-1935), the future nationalist dictator of Poland. Galicia is a geographic region spanning what is now southeastern Poland and western Ukraine. It is not the community in Spain of the same name.

In 1905, Grossman was part of a split of Jewish workers from the Social Democratic Party of Galicia, which formed the Jewish Socialist Party of Galicia.

After the Russian Revolution, he joined the newly formed Polish Communist Party, which sought to unite both the Polish and Jewish workers of Poland in a united revolutionary party of the working class.

In 1925, to escape the growing repression to which the Polish Communist Party was subjected, Grossman withdrew from the Communist movement and moved to Germany. There, he joined the Institute for Social Research in Frankfort, Germany, popularly known as the Frankfort School. At the Frankfort School, Grossman could concentrate on his interest in Marxist economic theory.

After Hitler rose to power in Germany in January 1933, Grossman was forced to flee the country. He initially found refuge in Britain and later in the United States. In 1949, the growing anti-Communist witch hunt in the United States forced him to leave. He found refuge in the newly formed German Democratic Republic – East Germany – in 1949. There, he joined the Socialist Unity Party. The Socialist Unity Party resulted from the merger of the German Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which formed the working-class party that ruled the newly formed German Democratic Republic (GDR). Grossman was appointed a professor of political economy at the University of Leipzig. He died in the GDR in 1950.

Today, Henryk Grossman is mainly remembered for his “The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System,” published in 1929. As the title suggests, the book is about the ultimate economic limits of the capitalist system. However, Grossman’s work has also had significant implications for the question of whether capitalism experiences cyclical or quasi-cyclical fluctuations longer than the ten-year industrial cycle. This is the question I want to explore in this chapter.

As we have seen, Marx, as early as the beginning of the 1850s, realized that the capitalist economy experiences a minor cycle of about three years’ duration in addition to a sharper cycle of about ten years – which Marx called the industrial cycle (the length of individual cycles can vary somewhat). In the United States, the term often used for the industrial cycle is “business cycle,” in Britain, it is “trade cycle.”

The shorter cycles that occur within the longer ten-year cycles have been noted by bourgeois business cycle experts as well as Marx. These cycles are sometimes called Kitchin cycles after the British businessman and statistician Joseph Kitchin (1861-1932) who described them. These short-term cycles are attributed to fluctuations in business inventories or fluctuations in the accumulation of commodity capital, using the more precise Marxist terminology.

Commodity capital consists of unsold commodities that have absorbed surplus value. The ten-year industrial cycle, in contrast, reflects fluctuations in the rate of accumulation of fixed capital such as factory buildings and machinery. Today, the downturns in the short-term inventory cycles have been re-christened “mid-cycle slowdowns” because they tend to occur in the middle of the industrial cycle.

However, some economists, both Marxist and bourgeois, have proposed since the turn of the 20th century that a longer cycle exists than the ten-year industrial cycle. This idea is most commonly associated with the Russian economist Nikolai Kondratiev (1892-1938), who gave an empirical description of the proposed cycle. Kondratiev claimed that this long cycle lasts about fifty years. Some Marxists, however, have expressed skepticism about the long cycle or rejected it outright.

Among Marxists who have rejected the existence of a cyclical movement of the capitalist economy longer than the ten-year industrial cycle were Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) and Paul Sweezy (1910-2004).

Neither Trotsky nor Sweezy denied the existence of long periods of rapid growth followed by periods of slower growth. On the contrary, they both affirmed that such periods exist. However, both Trotsky and Sweezy believed that the historical alternation of periods of rapid growth followed by slower growth was accidental rather than cyclical. Other Marxists have been far more receptive to the idea of a longer-than-ten-year cyclical, or at least quasi-cyclical, movement of the capitalist economy.

The two most well-known Marxist economists who have acknowledged the existence of at least a quasi-cyclical movement in the capitalist economy lasting considerably longer than ten years are Ernest Mandel (1923-1995) and Anwar Shaikh (1945-). Indeed, both Mandel and Shaikh wrote books dominated by a long cycle, or more cautiously, long-wave theory. (2)

Ernest Mandel’s most important writings that deal with what he called “long waves” are “Late Capitalism,” first published in German in 1972, and “Long Waves of Capitalist Development,” first published in 1980. Anwar Shaikh’s monumental “Capitalism Competition, Conflict, Crises,” first published in 2016, is centered on the “long cycle.”

However, the long cycle or “long wave” theory of Ernest Mandel and Anwar Shaikh rests mainly on the work of Henryk Grossman. Grossman, however, was not interested in whether long cycles in the capitalist economy exist but rather in another question. That question is about the ultimate economic limits of the capitalist economy and whether capitalism will eventually “break down” economically due to its inner economic contradictions.

The breakdown controversy

In the late 19th century, the young Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) was a very different party than the bourgeois-liberal labor-based party it is today. The belief was widespread in the SPD that there was an economic limit beyond which capitalism could not go. When capitalism approached this limit sometime in the future, a “commercial crisis” – as a cyclical crisis of overproduction was called in those days – worse than any other would occur.

This “final crisis” caused by the exhaustion of the world market would then trigger a political revolution, transferring power from landowners and capitalists to the working class, led by the Social Democratic Party. The conquest of political power by the working class led by the Social Democrats would enable the working class to transform capitalism into socialism. This view, known as the “orthodox Marxist” position, dominated the young Social Democratic Party of Germany.

Marx died in 1883, and in 1885, Marx’s co-worker, Frederick Engels, published Volume II of “Capital” based on Marx’s unedited drafts. While Volume I of Capital dealt with capitalist production – above all, with the production of surplus value – Volume II dealt with the circulation of capital. It took some years for the impact of Volume II to be felt. But when it was, a controversy was unleashed, which continues to this day.

Volume II contains mathematical tables of what Marx referred to as simple capitalist reproduction and expanded capitalist reproduction. Simple reproduction assumes that the capitalist economy remains unchanged in quantity and quality. The rate of surplus value, the organic composition of capital, the rate of profit, the level of employment, and industrial production do not change from year to year. In simple capitalist reproduction, there is no accumulation of capital, but there is the reproduction of the existing capital.

Marx divided capitalist production into two departments. Department I produces the means of production, and Department II produces the means of subsistence for both the workers and the capitalists. Marx’s model assumes a pure capitalist society where every person is either an industrial capitalist who lives off surplus value or a productive of surplus value worker with nothing to sell but their labor power. Department II is divided into two sub-departments. One sub-department produces necessities for both the working class and the capitalist class, while the other sub-department produces luxuries consumed only by members of the capitalist class. The model runs smoothly only if the correct proportion between Department I and Department II is maintained.

The necessary proportion is described by the simple equation CII = VI + SI:

- CII represents the constant capital of Department II

- VI represents the variable capital of Department I

- SI represents the surplus value of Department I

The terms in this equation represent definite quantities of abstract human labor measured by some unit of time that constitute the value of commodities. Every year, Department II consumes a certain amount of the plant, equipment, raw materials, and auxiliary materials.

On the use-value side, the terms of the equation represent specific use values measured in terms of units appropriate to their particular use values. However, different use values cannot be equated. Commodities with different use values can be equated by only one thing they have in common: they are both products of human labor. However, specific use values in definite proportions must be produced if the economy is to reproduce itself unchanged from year to year.

In use value terms, CII consists of means of personal consumption consumed by both the workers and the capitalists of Department I. VI and SI in use value terms consist of means of production, including raw and auxiliary materials that replace those used up by Department II during its production of the means of personal consumption that are consumed by both the workers and capitalists of Department I.

Marx assumes that all commodities are exchanged at their values. For the process of simple capitalist reproduction to run smoothly without crises or interruptions, the correct proportions must be maintained in terms of values to ensure the equivalent exchange of commodities and use values, which ensures that the physical process of reproduction proceeds smoothly. Any disproportions in value or use value will cause crises in the process of simple capitalist reproduction. Proportionality between values and use values must be maintained both between and within the two departments of production. However, Marx’s table only deals with the exchanges between the two departments of production.

Simple reproduction and circulation

In Volume II of “Capital,” Marx deals with the problem of reproduction. Circulation consists of the exchange of non-money commodities for money and the exchange of money for non-money commodities. Capitalist reproduction is, therefore, a unity between capitalist production and capitalist circulation.

A crisis in either capitalist production or capitalist circulation or between capitalist production and capitalist circulation means a crisis in the process of capitalist reproduction. However, most popularizations of Marx’s model of reproduction – both simple and expanded – abstract the whole question of circulation, defined as the exchange of commodities for money and money for commodities. This is what Grossman himself did in his reproduction tables.

However, Marx himself could not logically afford to abstract circulation because the chief subject of Volume II is the circulation of capital, not the production of capital. Over the decades, most popularizations of Marx’s model of simple reproduction simply abstract the question of the circulation of commodities in capitalist reproduction.

This tacitly assumes that the trade between Departments I and II is barter. The problem is when we do this, we build Say’s law right into our model of capitalist reproduction since, just like in Say, commodities are purchased by means of other commodities.

Models of reproduction, both simple and expanded, that abstract circulation allow crises of disproportionality to occur when too much of one type of commodity is produced while too little of another is produced. However, when we abstract the problem of circulation, we exclude a general overproduction of commodities. (3)

Therefore, models of capitalist reproduction that abstract money cannot possibly model a crisis of general overproduction. Marx’s models do not abstract circulation and therefore can form the starting point for analyzing the crisis of the general overproduction of commodities. They do this because they model the conditions necessary to avoid crises of general overproduction.

The question becomes whether such conditions can be maintained year by year or whether they can only achieved in the long run. Once we understand that the basic contradictions of commodity production mean that the conditions that allow expanded capitalist reproduction can be maintained in the long run – but not the short run – do we have a solid foundation to model periodic crises of the general overproduction of commodities.

However, in his tables of reproduction, Marx did not attempt to model crises of overproduction. In Volume II of “Capital,” Marx was interested in something else: We have to understand what conditions allow capitalist reproduction to proceed smoothly without crises. We cannot analyze crises without first understanding the conditions that allow capitalist reproduction to proceed without crises. Any deviation from these conditions will introduce elements of crisis.

The Problem of Circulation in Reproduction Models

In Marx’s table of simple reproduction, commodities are bought and sold for money. In Marx’s model, money consists of only full-weight gold coins. In the 19th century, when Marx worked on “Capital,” full-weight gold coins were used in circulation. If a gold coin fell below a certain weight, it was considered “light” and ceased to be legal tender.

This was necessary to prevent the price of gold bullion in terms of gold coins from rising above the par value. Experience showed that if light coins were allowed to remain in circulation, the light coins – representing “bad money” – would drive the full-weight coins – good money – out of circulation. The full-weight coins would either be hoarded or melted down into bullion. However, as capitalist production developed, the importance of gold coins in circulation progressively declined.

By the 19th century, gold coins formed a relatively small part of the circulating media in capitalist Britain – then the world’s most highly developed capitalist country – and were largely confined to retail trade. Banknotes – promissory notes issued by a bank payable to the bearer on demand in full-weight gold coins – and increasingly, bank checks were used by businesses to purchase expensive commodities from each other.

Cheap commodities sold in retail trade that today are purchased by paper money, fractional coins made of base metals, and increasingly by credit money that makes use of electronic bookkeeping (debit and credit cards as well as smartphones) were purchased by fractional coins made of base metals in 19th century Britain. At the time Marx was working on his reproduction tables, individual fractional coins made of base metals represented much more real money than such coins represent today. Most workers in Britain would likely go through life without ever seeing the lowest denomination banknote – the £5 note.

However, Marx’s assumption that all commodities are sold for full-weight gold coins, no matter how unrealistic it was for even the 19th-century British capitalist economy, is necessary to create a consistent mathematical table of simple reproduction that includes production and circulation. Marx assumed, which indeed was the case in reality, that in circulation, a certain percentage of the total circulating gold coins become light. This occurs because minute quantities of gold are rubbed off the coins whenever they are handled, reducing their weight slightly. Over time, the weight loss suffered by the individual coins becomes significant.

At that point, to avoid the depreciation of currency against gold bullion, the light gold coins had to be retired from circulation and melted into bullion and re-coined if a currency system that makes use of actual gold – and earlier, silver coins – is to function smoothly. (4)

If we are to imagine a system of simple capitalist reproduction, we have to assume that a certain amount of gold will be lost in circulation. Therefore, the industry that produces gold bullion as a commodity – mining and refining – must replace the gold bullion lost in circulation but no more.

Here, Marx considers only the gold bullion used for monetary purposes. Marx placed the gold bullion-producing industry in Department I, which is the production of the means of production because gold has other use values besides its monetary use value. However, as far as circulation is concerned, we are only interested in gold that functions as money material.

If capital accumulation is to run smoothly from year to year, both real capital and money capital – gold bullion – must be accumulated in the correct proportions. However, Marx’s simple reproduction model allows for no capital accumulation, either real or monetary. Therefore, neither the accumulation of real capital nor money capital is allowed.

If we allow the gold bullion-producing industry to produce a surplus of gold used for money material, we would have a net accumulation of money capital. This would no longer be a process of simple reproduction but an accumulation of money capital and, therefore, a model of the expanded reproduction of capital.

If the economy produced gold in inadequate quantities to circulate commodities, then simple reproduction would be disrupted because there would not be enough money to fully realize the value of commodities in terms of the use value of the money commodity.

Under these conditions, we would end up with contracted reproduction, not simple reproduction. If Marx had assumed that commodities were circulated by paper tokens representing a hoard of already existing gold, then simple reproduction could proceed smoothly without the need to produce money material.

However, Marx could not do this either because money must be an actual commodity. Since gold lasts forever on the scale of the lifetime of the capitalist mode of production – and, in reality, much longer money represented by tokens rather than gold coins would not have to be produced at all. But a commodity that is not produced is not a commodity at all.

Therefore, gold must be produced in Marx’s model of simple reproduction. Gold bullion must be represented in the table by full-weight gold coins in circulation. Marx’s table of simple reproduction is highly abstract and cannot exist in the real world. The reason is that in the real world, capitalism can only exist as a process of expanded, not simple, reproduction.

However – and this is very important – Marx realized that expanded capitalist reproduction must contain simple reproduction. You cannot hope to understand expanded capitalist reproduction without first understanding simple reproduction. Once a model of simple reproduction is grasped, the hard theoretical work has been completed. But a lot of painstaking and error-prone arithmetic – particularly in the days before computers – still lay ahead.

From simple to expanded capitalist reproduction

As long as we assume capitalist reproduction is simple, we assume that the capitalists spend their entire profit income on personal consumption for both necessities and luxuries. However, capitalist production cannot exist as merely simple reproduction. Capitalist production can only exist as expanded reproduction.

In expanded reproduction, the capitalists must invest a portion of their realized surplus value – profit – in expanding the level of production above the preceding reproduction cycle. The capitalists, therefore, must divide their profits into two parts. One portion they use to purchase means of personal consumption. The means of subsistence is divided into two parts. One part consists of necessities: commodities consumed by both capitalists and workers. The other part consists of items of luxury that are consumed by capitalists alone.

Once realized in the form of money profit, the remaining portion of the surplus value is re-transformed back into (productive) capital. A portion of new productive capital consists of variable capital. The money form of the variable capital is used to purchase additional labor power, which makes up the real form of the variable capital.

These newly employed workers then use their money wages to purchase the means of subsistence they need to live, reproduce their labor power, and produce still more surplus value for the capitalists. The capitalists use the rest of the money from the surplus value – profit – as new constant capital. The additional constant capital consists of new factory buildings, new machines, and additional raw and auxiliary materials needed to expand the scale of production in terms of value and use value. This process under capitalism creates what is commonly called economic growth.

Under expanded capitalist reproduction, Department I must trade its increased commodity capital for increased means of personal consumption, both necessaries and luxury commodities produced by Department II. The increase in production of means of production in Department I must, in terms of value, match the increased production of means of personal consumption in Department II. This must be done in proportions that enable the continuation of equivalent exchanges where one commodity of a certain value is exchanged for another commodity of the same value while also maintaining the necessary proportionality in terms of use values that enable production to grow in physical terms.

Circulation and expanded capitalist reproduction

Under simple capitalist reproduction, the market does not expand. The industry that produces money material needs only to replace the money material lost in circulation. However, under expanded reproduction, the markets for commodities must expand to meet the rising production of commodities.

Therefore, there must be a proportional increase in the amount of gold bullion – money material – which makes the additional means of circulation possible to accommodate the increased volume of commodities.

If too little gold is produced, there will not be enough additional means of circulation to accommodate the increased quantities of commodities at their full value. Money will be in short supply as a means of purchase and payment, pushing up interest rates. If too much additional gold bullion is produced relative to a rise in the production of non-money commodities, the extra money will accumulate in stagnating idle hoards, causing the rate of interest to fall towards the mathematical limit of zero.

Marx’s model of expanded reproduction keeps the rate of surplus value, the organic composition of capital, and the rate of profit unchanged while providing for an adequate expansion of the quantity of money material, which makes possible an adequate expansion of the market to sell the ever-increasing quantities of commodities at their values. (5)

The assumptions of Marx’s tables of expanded capitalist reproduction

In Marx’s model of expanded reproduction, the capitalist economy changes quantitatively – it constantly grows in size – but does not change qualitatively. The rate of surplus value, the rate of profit, the value of non-money commodities as well as the value of money all remain unchanged. However, the total quantities of constant capital, variable capital, money material, surplus value, and profits – the money form of surplus value – rise continuously at a constant rate of change. The accumulation of real capital is, therefore, matched by a proportionate accumulation of money capital.

Marx’s model of expanded capitalist reproduction has an interesting mathematical quality. If we write a computer program that performs the necessary calculations and run it on a computer with infinite memory, the program runs forever.

Before Marx, only one other economist had tackled the problem of reproduction. That economist was the French Physiocrat Dr. François Quesnay (1694-1774), who in 1758 published his “Tableau économique” and whose work can be considered the forerunner of Marx’s work on reproduction.

Political impact of Marx’s tables of expanded capitalist reproduction

The publication of Volume II of Capital by Frederick Engels in 1885 took some time to become known among the Marxist public. When it did, the political impact was felt first in Russia.

At the time of the publication of Volume II of “Capital,” the revolutionary movement in Russia was dominated by populists who later formed the Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party. The Russian populists argued that in Russia, which as late as the 1880s was still a largely pre-capitalist country, capitalism would not be able to develop. According to the populists, developed capitalist countries had already monopolized the world market.

Therefore, potential Russian capitalists would be unable to find markets for their commodities. The populists concluded that modern communism would come to Russia, not through an era of capitalist development like in the West, but rather through the peasant commune, which preserved elements of common ownership of the land and the performance of agricultural tasks in common. These formed a historic remanent of the clan-tribal communist past. According to the populists, in Russia, it would, therefore, be the peasantry, not the proletariat, that would be the chief agent of the socialist revolution.

However, contrary to the populist predictions, by the 1890s, capitalism was taking hold in Russia. As a result, some former populists broke with populism and embraced Marxism. These pioneer Russian Marxists were led by former populist Georgi Plekhanov (1856-1918).

Plekhanov and his supporters argued that capitalism was developing in Russia and would continue to do so. This, Plekhanov and his supporters argued, would complete the destruction of whatever was left of the communism of the peasant commune. The Russian Marxists cited Marx’s models of expanded reproduction, as presented in Volume II of “Capital,” to address the populists’ objections that capitalism would never take root in Russia due to a lack of adequate markets.

Plekhanov held that as long as the proper proportions of the various branches of production were maintained, especially the relationship between Department I and Department II, the market would grow as the production of commodities expanded, just as it does in Marx’s models.

Therefore, the Russian Marxist argued that the lack of markets would not be a barrier to the development of capitalism in Russia. According to the pioneer Russian Marxist, contrary to the populists, Russia would only reach modern communism by passing through a process of capitalist industrialization that would create a growing proletariat.

Once Russian capitalism was sufficiently developed, the proletariat would overthrow capitalist rule and lead a Russian socialist revolution. Russia was viewed as approaching a bourgeois revolution that would remove pre-capitalist obstacles to further capitalist development. Then, after enough time had passed to allow Russia to reach a high level of capitalist development, the Russian socialist revolution would occur.

While the Russian populists formed the Socialist-Revolutionary Party, the Russian Marxists formed the Social-Democratic Labor Party. Therefore, Marx’s reproduction schemes in Volume II of Capital played a crucial role in the birth of Russian Marxism, which played an outsized role in the 20th-century workers’ movement and the development of Marxist thinking throughout the world during the 20th century.

The impact of Marx’s reproduction schemes in Germany

In Germany, the impact of Marx’s reproduction tables was felt no less profoundly. In contrast with Russia, German capitalism had already reached a high level of development by the last part of the 19th century. Therefore, there was no German populist movement that argued that capitalism could not develop in Germany. In Germany, the question was not whether or not capitalism could develop. It had.

The question in Germany was how long capitalism could last. As we saw above, one feature of Marx’s expanded reproduction tables is that they run forever. In these tables, there is no “final crisis” of capitalism – or indeed any crises at all.

Marx’s model is based on the assumption that the necessary proportionality between Department I and Department II is maintained, as well as the proportionality between the industry that produces money material and all other industries. These proportionalities are maintained by the struggle of industrial capitalists operating in different industries for the maximum possible profit.

The resulting anarchy of production allows countless possibilities for disproportionate development between the two departments of production and within them. It also allows possible disproportions between the industry that produces money material and the industries that produce all other commodities.

However, these disproportions are resolved through the process of capitalist competition and the resulting tendencies of the equalization of the rate of profit. Through anarchic competition, the law of value asserts itself. As the law of the value of commodities asserts itself, the order of expanded capitalist reproduction emerges out of disorder. Because Marx’s models of reproduction run forever, they began to undermine the expectation of a “final crisis” of capitalism among the German Social Democrats.

A tendency emerged that viewed economic crises as arising from accidental disproportions between Department I and Department II, which temporarily disrupted the process of capitalist expanded reproduction. Marx’s treatment of money and monetary circulation in his reproduction models seemed to be merely an unnecessary complicating element that could be disposed of for simplification.

It was obvious that Marx’s assumption that all commodities are sold for full-weight gold coins contradicted reality. Most commodities were not purchased with full-weight gold coins but by other means of circulation that represent gold in circulation.

As we saw above, once we abstract money from Marx’s reproduction models, we arrive at Say’s Law. In these simplified versions of Marx’s models that abstract money, commodities are purchased by means of commodities, as in Say’s Law. While disproportionate production, whether between Department I and Department II or within the departments, can lead to some types of commodities being overproduced relative to others, no general overproduction of commodities is possible.

In addition to the declining role of gold coins in circulation, it seemed to many in the German Social Democratic Party that capitalism was becoming better organized as the importance of banks, cartels, syndicates, and trusts grew. The final years of the 19th century were a time of great capitalist prosperity and the consequent high and growing demand for the commodity labor power.

These conditions were highly favorable for the growth and strengthening of labor unions and the Social Democratic Party in Germany, and to a lesser extent, in other countries. The Social Democratic parties, as the Marxist parties were then known, were able to utilize the growing strength of labor unions to win an increasing number of votes in parliamentary elections and thus elect an ever-growing number of deputies to parliament.

A revisionist current emerged in Germany in the late 1890s, following the death of Frederick Engels in 1895. The revisionists argued that crises resulted from the immature conditions of early capitalism. As capitalism became better organized, accidental disproportions became less serious. Therefore, the revisionists argued that there was no reason why the capitalist prosperity of the late 1890s could not continue indefinitely.

Instead of revolution brought on by a final crisis of capitalism, the revisionists argued the prospect was for an ever-growing series of reforms that would be in the interest of the working class. According to the revisionists, socialism was a moral idea, not an economic necessity. The revisionists concluded that the Social Democratic Party should stop pretending to be revolutionary. Instead, as it was becoming in practice, it should declare itself a party of reform.

Marx’s reproduction tables, Rosa Luxemburg, and the revisionists

These developments alarmed Rosa Luxemburg, a Polish immigrant of Jewish origin in Germany, who was emerging as a key figure in the left wing of the German Social Democratic Party. Once she became fully aware of Marx’s reproduction tables in Volume II of Capital and the impact they were having on the German and international Social Democratic movements, Luxemburg attempted to overthrow them.

In her book “The Accumulation of Capital” (first published in 1913), Luxemburg attempted to prove that, in a pure capitalist economy consisting only of capitalists and workers, the realization of surplus value and, therefore, expanded capitalist reproduction, was mathematically impossible.

According to Luxemburg, the continued existence of non-capitalist modes of production was not merely a relic of the past but an absolute necessity for capitalism. However, since the development of capitalism inevitably led to the destruction of all pre-capitalist modes of production, it would only be a matter of time before capitalism would economically collapse due to the permanent exhaustion of the world market.

Over the more than a century since Luxemburg published the “Accumulation of Capital” in 1913, only a few Marxists have defended her views. The most famous Marxist who rejected Rosa Luxemburg was the Russian Marxist V.I. Lenin, the founder of the Bolshevik Party – later the Communist Party- and leader of the Russian October Socialist Revolution. Luxemburg’s arguments reminded Lenin of the arguments of Russian populists, who the pioneer Russian Marxists, including the young Lenin, had refuted.

Otto Bauer deepens Marx’s model of expanded capitalist reproduction

What turned out to be the most important criticism of Luxemburg’s “The Accumulation of Capital” came from the Austrian-Marxist Otto Bauer (1881-1938). Bauer was one of the most capable of the Social Democratic theoreticians. Bauer’s answer to Luxemburg was to have broad and lasting influence, though not quite the way Bauer expected.

The limits of Marx’s model of expanded reproduction are that it only deals with the quantitative growth of the capitalist economy and not its qualitative growth. Marx presented his model of expanded reproduction in Volume II of Capital before presenting his law of the rise in the organic composition of capital, the transformation of values into prices of production through the equalization of the rate of profit, and, most importantly, the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. These are dealt with only in Volume III of Capital.

Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall flows not from the quantitative development of capitalist expanded reproduction but rather the qualitative development of capitalism expressed in the growth in the productivity of labor expressed through the rise of the organic composition of capital. To the best of our knowledge, Marx did not attempt to develop a table of expanded reproduction that included a rise in the organic composition and a fall in the rate of profit. This task fell to Otto Bauer.

Bauer was an Austrian Social Democrat belonging to the “Austro-Marxist tendency” within the broader German-speaking Social Democratic movement. The Austrian Marxists, mainly from German-speaking Austria in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1867–1918), were considered centrists within the Social Democratic parties. They were halfway between the revolutionary left wing and the revisionists to their right.

Unlike the revisionists, the Austrian Marxists considered themselves orthodox Marxists and often employed revolutionary-sounding rhetoric. But when the time for revolutionary action arrived, they were not there. They inclined toward the view that capitalism would evolve into socialism through gradual, peaceful economic development, parliamentary democracy, and a peaceful conquest of political power by Social Democracy through elections and parliamentary means.

Bauer was considered a leader of the left wing of the Austrian Social Democratic Party. However, after the 1917 Russian October Revolution, Bauer, typical of the Austro-Marxists, remained a member of the Second International of the Social Democrats and the Austrian Social Democratic Party. In 1934, Austrian chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss (1892-1934) moved to crush the Austrian Social Democratic Party by force and establish dictatorial rule. Bauer was forced to flee Austria, first to Czechoslovakia and then to Belgium. He died in Paris in 1938.

What Bauer did in 1913 was to extend Marx’s model of expanded reproduction by taking into account both a rising organic composition of capital and a consequent fall in the rate of profit while keeping all the other factors that Marx held constant, unchanged. Since capitalism is a system of production for profit, a falling tendency in the rate of profit, which arises from the development of capitalism itself, implies that capitalism must be replaced by a higher mode of production sooner or later.

However, Marxist opponents of what became known as the “breakdown” theory pointed out that the fall in the rate of profit is compensated by a growth in the mass of profit. Even Rosa Luxemburg accepted this argument.

The falling rate of profit and the future of capitalism

The classical bourgeois economists had generally assumed that the historical trend of the rate of profit was downward. Adam Smith believed that as capital continued to accumulate, increased competition among the capitalists would drive down the rate of profit. David Ricardo rejected Smith’s explanation of the downward trend in the rate of profit. According to Ricardo, competition among capitalists can lower the rate of profit in various industries, but this is only a temporary effect.

However, Ricardo agreed that the trend of the rate of profit is indeed downward. Ricardo believed that as capitalism developed and the population grew, all the most fertile land would eventually be fully brought into cultivation. After that, poorer and poorer land would have to be cultivated. This would increase differential rents and force up money wages because higher money wages would be necessary to cover the rising price of food.

This would mean, to use Marxist terminology, that the rate of surplus value would decline – with the real wage remaining unchanged – while an increasing amount of the surplus value that was still produced would go to the landowners in the form of ground rent as opposed to the capitalists in the form of profit. Eventually, the falling rate of profit would bring further capitalist development and human progress with it to a halt. Ricardo hoped that this was still a long way off.

Marx agreed that the tendency of the profit rate was downward but gave a completely different explanation than Ricardo’s. Capitalist competition, Marx explained, forces individual industrial capitalists to cheapen their products by replacing workers with machinery. Marx called the physical ratio of machines, raw materials, and auxiliary materials to living labor the technological composition of capital.

Assuming the value of the workers’ wages remains unchanged, the ratio of the value of all elements of capital other than the purchased labor power of the workers would rise. Marx called the ratio of all elements of the productive capital to purchased labor power the organic composition of capital. To the extent that changes in the composition of capital reflect the increasing value of the total constant capital relative to the total variable capital, the organic composition of capital rises.

The ratio determining the organic composition of capital is a ratio of values – labor embodied in commodities performed in the past. Since the fall in the quantity of labor needed to produce a given element of constant capital – a factory machine, for example – falls with the growth in the productivity of labor, the organic composition of capital rises more slowly than the technological composition of capital.

However, Marx believed that organic composition does rise. Since it is only living labor – labor power purchased by the industrial capitalists called variable capital by Marx – that produces surplus value, a rise in the constant capital combined with a given rate of surplus value will mean a fall in the rate of profit when calculated on the total advanced capital. Even a rising rate of surplus value combined with a rise in the organic composition can lead to a falling rate of profit. However, a rising rate of surplus values counteracts the downward pressure on the rate of profit exerted by a rising organic composition of capital.

Marx believed that despite the tendency of the rate of surplus value to rise and despite the operating of other countervailing forces, such as the cheapening of the elements of constant capital, the rate of profit would tend to fall over long periods. Marx based his law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall not due to the effects of competition as Adam Smith had, nor on external forces like the limit on the quantity of rich agricultural land as Ricardo had, but on the development of capitalist production itself.

Marxists of the Second International era, such as Rosa Luxemburg, who defended the view that the economic breakdown of capitalist production was inevitable, focused on the difficulties of realizing surplus value rather than the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

The downward tendency of the rate of profit was offset by the rise in the mass of profits, which was an observable fact reflected by the upward march of stock market prices. There is no contradiction between reading on the financial pages that corporate profits set a new record in the last quarter and the long-term tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

The capitalist mode of production is a system in which an ever-growing number of workers produce an ever-greater mass of surplus value. The substance of surplus value is unpaid labor measured by some unit of time. Its form is profit, measured in terms of the use value of the money commodity. Therefore, there is no contradiction between a falling tendency in the rate of profit – and outside of recessions – the fact that corporations make record profits quarter after quarter.

On the contrary, this is the basic law of motion of the capitalist mode of production – a gradually declining rate of profit to be compensated by a rise in the mass of profit. The rising mass of profit – reflected in rising stock market prices – results from the ever-rising number of workers exploited by capital.

Since the fall in the rate of profit is compensated by a rise in the mass of profit, most of the Marxists of the era of the Second International preferred to look to problems that arise in the sphere of circulation, of realizing surplus value, rather than the problems of producing of surplus value in explaining both the causes of periodic economic crises and the ultimate limits of capitalist production.

However, this was not necessarily Marx’s view. Grossman quotes Marx:

“The same development of the social productiveness of labor expresses itself with the progress of capitalist production on the one hand in a tendency of the rate of profit to fall progressively and, on the other, in a progressive growth of the absolute mass of the appropriated surplus-value, or profit.” (“Capital Vol. III, Part III. The Law of the Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall, Chapter 13. The Law As Such.” From Marxists Internet Archive.)

Marx noted that Ricardo feared that the “motive for accumulation will diminish with every diminution of profit, and will cease altogether when [the capitalists’] profits are so low as not to afford them an adequate compensation for their trouble and the risk they must necessarily encounter in employing their capital productivity.” (“Law of the Accumulation and Breakdown,” Henryk Grossman 1929.)

Despite Marx’s hints to the contrary – which we will examine when we get to the breakdown theory proper – most Second International-era Marxists held the tendency of the rate of profit to fall with the development of capitalism did not represent any threat to the virtual indefinite continuing existence of capitalism.

In his answer to Rosa Luxembourg’s “Accumulation of Capital,” Otto Bauer was determined to refute the idea that capitalism faced any problem of finding adequate markets for the ever-greater quantity of commodities that the industrial capitalist could produce. He was also determined to prove that the fall in the rate of profit represented no threat to the virtual indefinite continuation of capitalism.

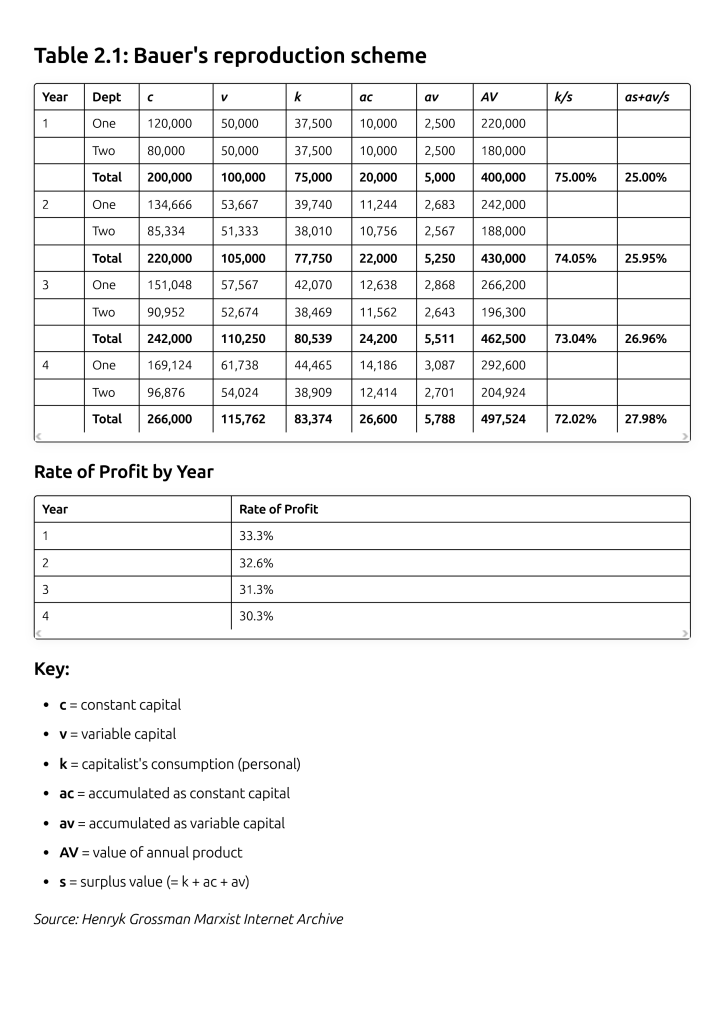

Otto Bauer produced the following table, which is reproduced below.

In constructing the table, Bauer made several assumptions. He assumes that every worker seeking work will find it. The working-class population is growing at a rate of 5% per year, so capitalists must expand employment by 5% per year. Bauer holds the rate of surplus value and value wage – but not real wages – constant. Unlike later neo-Ricardian models, Bauer does not hold the real wage constant. Like Marx in his reproduction models and much of the rest of Marx’s work, Bauer deals with values, not use values like modern neo-Ricardians do.

However, unlike Marx’s reproduction model of expanded reproduction, Bauer’s model assumes that constant capital in value terms grows at twice the rate of variable capital. This implies a steady rise in the productivity of labor.

Since Bauer assumes a stable rate of surplus value of 100% – the workers work half the work day for themselves and half the day for the capitalists – Bauer’s table implies a steadily rising real wage. The real wage rises with the growth in labor productivity, but the value of the wage the workers receive in return for their sold labor power remains unchanged. From the workers’ viewpoint, life improves as capitalism develops. There is neither any absolute nor relative impoverishment. Nor is there any unemployment problem.

Since the rate of surplus value and the value wage is held constant by Bauer, to fully employ all the new workers that are entering the labor market due to the growth of the working population at the assumed rate of 5% per year, variable capital measured in terms of its value must also grow at a constant rate of 5%.

However, as we have seen, unlike Marx’s model, Bauer’s model assumes that constant capital is growing twice as fast as variable capital. This means that the variable capital must continue to grow at 5%, while variable capital represents an ever-smaller portion of the total capital.

Therefore, to maintain a constant rate of growth of variable capital, the accumulation of capital must continuously accelerate. Since the rate of accumulation is defined as the ratio of the profit that is (re)transformed by the capitalists into new (productive) capital relative to the portion of the profit used for personal consumption, the capitalist class is left with an ever smaller percentage of total profits to satisfy their personal consumption needs.

Unlike Marx’s tables of expanded capitalist reproduction, Bauer’s expanded reproduction model includes a falling profit rate. In Bauer’s table, the rate of profit falls because of the rise in the organic composition of capital combined with a constant rate of surplus value. The rate of profit is 33.33% for the first year, but by the fourth year, the rate of profit has fallen to 30.3%. Bauer, however, thought that his table had shown that the fall in the rate of profit would present no real problem for the capitalists and the capitalist system.

Like Marx, Bauer extends his calculations – a rather laborious task in the pre-computer era – over four years just as Marx did in his tables. Since the capitalists are required by the table’s assumption to create 5% more jobs yearly, they must spend an ever-increasing portion of their total profit on accumulating additional capital, leaving less profit to meet their personal needs.

While in year one, Bauer’s table allows capitalists to consume 75% of the total surplus value for personal consumption; by year four, they are allowed to consume only 72.02%. However, since the number of workers producing surplus value for the capitalists is rising year by year at a constant rate of 5%, the quantity of surplus value consumed by the capitalists for personal consumption rises in value terms by 11.7%. Therefore, over the four years that the Bauer table runs, once we take the rising productivity into account, in use value terms, the rise in capitalist consumption will be considerably greater than 11.7%, though nothing in the table allows us to make an exact calculation.

Therefore, the material needs of the capitalist and working classes are met. The workers’ real wages rise with productivity, and all members of the young generation entering the labor market for the first time have no difficulty getting jobs. While the capitalists do experience a slight fall in their rate of profit, in terms of their consumption, they are consuming in absolute terms more surplus value than ever in terms of value and even more so in terms of use values.

In Bauer’s tables of expanded reproduction with a rising organic composition of capital and a falling rate of profit, there is no economic reason to expect the class struggle to sharpen over time. The rate of exploitation of the working class does not increase at all, while the standard of living of the working class grows with the advancement of the productivity of labor. All the while, full employment is maintained. All while what we assume is an already ample standard of living for the capitalist class also rises. Any U.S. president who claims to represent “all of the people” would be delighted to run for reelection on such a record.

Bauer’s fatal mistake

Like Marx, Bauer carried out the painful arithmetic for four periods or years. Marx could have made his point by carrying out the calculation for only two years, or he could have made his point by carrying out the calculation for an infinite number of years if he had an infinite amount of time. The reason is that a mathematical quality of Marx’s reproduction tables is that they run forever in what computer scientists call an infinite loop. But Bauer, for all his theoretical ability, was not a good mathematician. Bauer perhaps assumed that if Marx’s tables indeed ran forever, his would do so as well. But mathematics says otherwise. The person who noticed this fatal flaw in Bauer’s demonstration was Henryk Grossman. By the time Grossman was through with Bauer’s table, what Rosa Luxemburg called Bauer’s “neo-harmonist” conclusions were in ruins.

In the first four years of Bauer’s tables, the capitalists’ consumption, though it declines relative to the amount of productive consumption, increases absolutely over the four years. In the tables, capitalists consume commodities worth 75,000 hours of labor during the first year. By the fourth year, it’s 83,374 hours of value. Everything appears to be proceeding well.

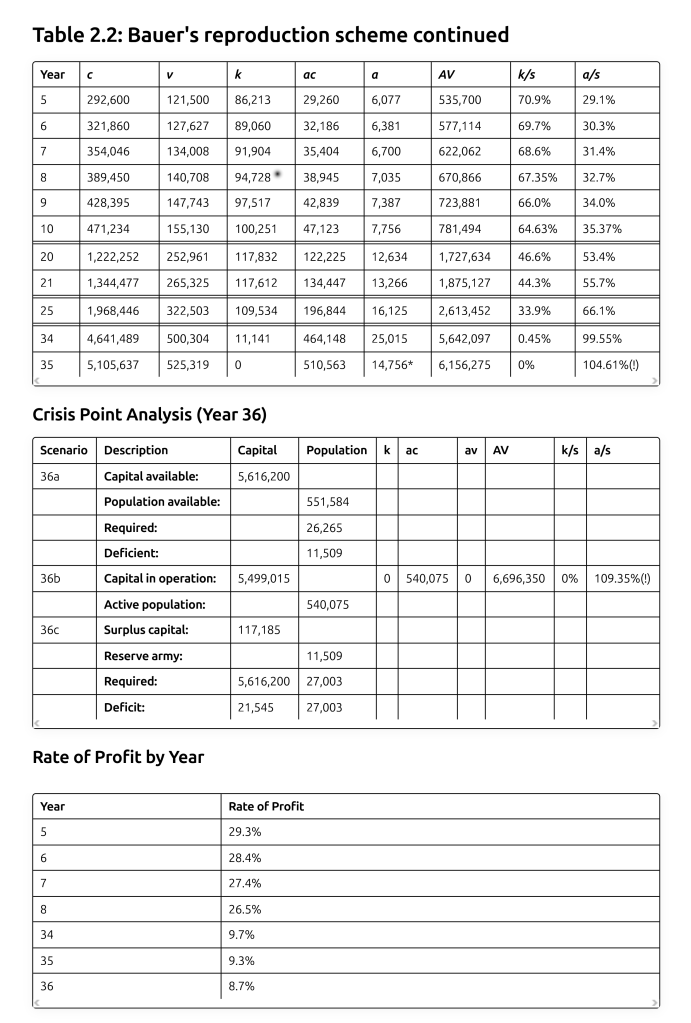

However, Henryk Grossman later came along and, in 1929, extended Bauer’s table to run not four years but 36 years.

(Source: Marxists Internet Archive Henryk Grossman)

At the end of Grossman’s extension of the Bauer model, the profit rate fell from 29.3% in year five to 8.7% in year 36. At first glance, it would seem that an 8.7% rate of profit in the 36th year, though far lower than 29.3% in the fifth, should still be ample enough once we consider that a vastly greater mass of surplus value is produced in the 36th year.

However, according to Bauer’s assumptions, to keep variable capital accumulation in the face of a rising organic composition at a rate sufficient to employ 5% additional workers every successive year to match the 5% increase in population means the rate of accumulation must also progressively increase.

In the table reproduced above, the portion of the surplus value not accumulated but left over for capitalist personal consumption is represented by the letter k. The value of k rises from 86,213 to 117,832 in year 20. Even though a portion of the surplus value reserved for the personal consumption of the capitalists (represented by the letter k) shrinks relatively to the portion of the surplus value accumulated, the personal consumption measured in terms of value increases absolutely. This is fully in line with what Bauer was attempting to prove.

However, in year 21, the value of k decreases from 117,832 to 117,612. To keep the growth rate of the organic composition steady while also maintaining a 5% increase in variable capital, the surplus value available for capitalists’ consumption starting from year 21 — after meeting the growing needs of accumulation — will drop not only as a percentage of the total surplus value but also in absolute value terms.

This might not be too bad for the capitalists as we are measuring the value of k in terms of hours of labor — not of use values, which is what interests the capitalists in their role as personal consumers. But after the 21st year onward, the value of k keeps falling yearly. In year 35, k has fallen to below zero. While we can infer that the enhanced productivity of labor has significantly reduced the value of individual consumer goods — both necessary and luxury items consumed by capitalists — compared to what they were in year 1, these goods still represent some labor.

Zero hours of labor means a zero quantity of use values. By the 35th year, the capitalists will have to live on air!

Even if the capitalists can somehow pull off this trick by the 35th year, it has become impossible to maintain the growth rate of variable capital at 5% a year, which is necessary to maintain full employment even if the capitalists refrain from all personal consumption. They would have to accumulate 104.61% of the available surplus value – a clear mathematical impossibility.

Merging Bauer’s initial table, which spans from year one to year four, with Grossman’s extension from year five to year thirty-six, we observe that by year thirty-five, the total surplus value increases from 100,000 to 525,319 (measured in some unit of time). That is, the total quantity of surplus value produced increases more than fivefold. However, despite the more than fivefold increase in the total amount of surplus value, the Bauer-Grossman model collapses due to an insufficient quantity of surplus value produced. By year 35, even if the personal consumption of the capitalists falls to zero and all surplus value is (re)transformed into new capital, there will still not be enough variable capital to fully employ all the workers seeking employment. The insufficient quantity of surplus value is due to the increasing demands of accumulation of constant capital outpacing the growth in surplus value production.

Unlike Marx’s model, which assumes a constant organic composition with a constant rate of profit, the Bauer model assumes a rising organic composition of capital with a falling rate of profit that does not run forever. It only lasts for a limited number of years.

The mathematics of the Bauer-Grossman model indicates that it can only continue beyond the 35th year if we modify the numbers we input into the table. We can “reboot” the model by increasing the rate of surplus value. At the higher rate of surplus value, the model will again run for a while but will break down in the end as the quantity of the total surplus value left over for capitalist personal consumption after the needs of accumulation are met again falls to zero. This rebooting process can occur multiple times, but ultimately, the model will fail as the surplus available for workers’ wages approaches the mathematical limit of zero.

The model can also be further extended if we reduce the rate of increase of the organic composition of capital. Bauer assumed that constant capital grows at twice the rate of variable capital. But this assumption is arbitrary. If we reduce that rate, the number of years that the model runs increases. However, the model will still break down after a finite number of years as long as we assume a constant rate of increase in the organic composition of capital.

Only if we reduce the growth in the organic composition of capital to zero, as Marx did in his tables, will the model run forever. Contrary to his intentions, Bauer unwittingly revealed a deep contradiction between the rise in labor productivity expressed through a rising organic composition of capital on one side and, on the other side, a capitalist system based on exploiting an ever-rising number of wage workers to produce ever greater quantities of surplus value.

The Bauer-Grossman model and long cycles of capitalist development

The Bauer-Grossman model can be seen as demonstrating that the capitalist system has to break down sooner or later as long as we assume a rising organic composition of capital. But, the relationship between the Bauer-Grossman model and actual economic fluctuations in the capitalist economy is another question entirely. The Bauer-Grossman model, with the numeric values provided by Bauer but taken to its conclusion by Grossman, where k represents capitalist personal consumption, falls below zero in the 35th year, is an impossible situation in the real world. How quickly capitalism collapses in a Bauer-Grossman table depends on how quickly the organic composition of capital increases, the rate of surplus value is allowed to rise, and the rate of growth of the working-class population.

The model runs longer if we drop the assumption of “full employment” – and in reality, the capitalist mode of production is incompatible with genuine full employment. Bauer’s ridiculous assumption of full employment does not accurately reflect capitalist reality.

In the Grossman-Bauer model, capitalism can continue to exist beyond the 35th year with a rising level of unemployment. However, the value of v – the total wages paid to workers – can never drop to zero. If it did, according to the laws of mathematics, if we attempted to divide the total value of the constant capital by the total value of variable capital to calculate the organic composition of capital, the result would be undefined because we would be dividing zero by zero.

If no living labor is employed, all the constant capital can be reproduced with zero labor. This would mean that the value of constant capital calculated in hours of labor would be zero. Variable capital would also be zero.

This is another tipoff that we are dealing with an impossible situation. If this were possible, all workers would be unemployed, and the capitalists would live on air. Or, more realistically, capitalist production, which at its core is a process where an ever larger number of wage workers perform unpaid labor for a class of capitalists, will have long since been superseded.

The strength of the Bauer-Grossman model lies in its ability to demonstrate that, despite starting with unrealistic assumptions such as “full employment” and a fixed rate of surplus value, it ultimately reflects the characteristics of real-world capitalism. This includes the emergence of a reserve industrial army and a rising rate of surplus value without even considering the problems posed by the circulation of commodities. When pursued to its logical conclusion, the model indicates that capitalism — characterized by the extraction of surplus value from a class of wage workers by a class of capitalist exploiters — must eventually disappear as the productive forces continue to develop. However, it remains unclear how effectively the Bauer-Grossman model can serve as a framework for understanding actual cyclical real-world capitalist crises.

The reason is that the Bauer-Grossman table deals only with the production of surplus value and not with the realization of surplus value, which is taken for granted in the table.

Put another way, the model deals with the production of commodities and surplus value but ignores the problems of the circulation of commodities and the realization of surplus value in the form of profit that must be measured in terms of the use value of the money commodity.

In Marx’s tables of simple and expanded reproduction presented in Volume II of Capital, simple and expanded capitalist reproduction is the necessary unity of capitalist production and circulation. Marx’s table of reproduction, which includes circulation, specifically addresses scenarios only where the organic composition of capital, the rate of surplus value, and the rate of profit remain constant.

Marx’s table of reproduction possesses a potential power that the Bauer-Grossman tables, despite their strengths, lack.

It is tempting to see the Bauer-Grossman tables as modeling not the 10-year industrial cycle but rather the proposed 50-year-long cycles or, if you prefer, “long waves.” We see this approach in Ernest Mandel’s “long waves” and Anwar Shaikh’s model of long cycles.

Chronologically, Ernest Mandel’s work preceded Shaikh’s work and inspired it. But logically, we have to deal with Shaikh’s first because Shaikh’s theory, as presented in his 2016 “Capitalism,” is a far more consistent development of Grossman’s work than Mandel’s. We will, therefore, begin with Shaikh and finish with Mandel.

Shaikh, in “Capitalism,” does mention the existence of the “business cycle,” which corresponds with Marx’s “industrial cycle,” but gives it virtually no attention. I believe the reason is that Shaikh accepts the claim that “modern money” is non-commodity money. His failure to analyze money correctly prevents Shaikh from successfully analyzing the circulation of commodities and the realization of surplus value.

Marx considered non-commodity money (defined as money that does not represent a specific money commodity) impossible under the system of commodity production. However, Shaikh doesn’t understand this. Based on his incorrect theory of money, Shaikh concludes that the capitalist state, which includes the government and the central bank working together with the commercial banking system, can create any demand it desires.

As far as Shaikh is concerned, there are no limits beyond which the market can expand. This excludes the view of Marx and Engels that crises of the general overproduction of commodities are inevitable once capitalism reaches a certain level of development. While Marx and Engels saw cyclical capitalist crises as crises of overproduction, Shaikh does not. Except when directly quoting Marx, the word “overproduction” is virtually absent in Shaikh’s “Capitalism.”

However, Shaikh’s theory does not exclude the possibility of a general crisis of overproduction. Even non-commodity money does not exclude that a commodity can be sold for money that is not immediately spent. Following Shaikh’s logic under the previous systems of commodity money – the silver and gold standards – problems of realizing surplus value perhaps arose, though Shaikh has little to say about it. Following Shaikh’s logic under a system of non-commodity money called “pure fiat money” by Shaikh, circulation problems can only arise due to mistakes by the government and central bank – which are, of course, possible – or if the government or central bank wishes to induce a higher rate of unemployment to increase the rate of exploitation of the working class.

However, once “pure fiat money” is introduced, problems arising from the difficulties of circulation will be superficial. If problems of realizing value and surplus value do arise, they can be easily dealt with through the now well-known “Keynesian” techniques of the central bank accelerating the rate at which it creates new money and increasing central government borrowing and spending of money to make sure the newly created non-commodity money circulates and does not accumulate in stagnate hoards.

In Shaikh’s view, since the creation of “pure fiat money” was always a policy option, if not a policy practice, the problems of the realization of the value of commodities, overproduction, and circulation can be viewed as easily solved within the framework of capitalism. To this extent, the mature Shaikh is a “Keynesian.”

However, in Shaikh’s view, the production of surplus value is another question entirely. Surplus value that is not produced cannot be realized. In Shaikh, it is not enough for the capitalists to maintain a given rate of surplus value. As capitalism develops, the surplus value rate must rise to stave off the fate that awaits it in Grossman’s extended version of Bauer’s reproduction table. If the rate of surplus value fails to rise or rise sufficiently, the rising organic composition of capital will cause the rate of profit to fall. Once the rate of profit starts to fall due to a rise in the organic composition of capital, it is only a matter of time before economic growth slows down and unemployment rises.

Following Shaikh, a crisis caused by a fall in the profit rate caused by the rise in the organic composition with a given rate of surplus value cannot be overcome by the “Keynesian” methods of pumping up demand with the aid of non-commodity money. It can only be overcome by increasing the rate of surplus value.

However, when investment does slow down, circulation problems will likely arise as a side effect. Because the industrial capitalists cannot find sufficient profitable fields for investment, they will hold on to M – even if M represents non-commodity money – rather than transform the M into new productive capital – M..C — P — C’..M’. (6)

At this point, the crisis appears to be a crisis of overproduction. But it is really a crisis of the insufficient production of surplus value. If the rate of surplus value rises sufficiently, the problems of circulation will go away because the industrial capitalists will stop holding on to M and, now that they are making adequate profits again, engage in reproduction on an extended scale.

Shaikh believes that faced with slow or no growth, rising politically destabilizing unemployment, the capitalist state and central bank may turn toward Keynesian policies in an attempt to boost economic growth once again and reduce unemployment. If the crisis is superficial – caused by the failure of the central bank to create enough money – which was all too likely under the gold or gold-exchange standards of the past – the crisis can easily be overcome by increasing the quantity of new money that the central bank creates and if necessary through deficit spending by the central government that prevents the new non-commodity money from falling out of circulation and accumulating in stagnant hoards.

However, if the crisis is profound – meaning that the apparent overproduction is simply a reflection of insufficient production of surplus value – Keynesian policies will fail. True, a policy of monetary inflation by the central bank will stop the industrial capitalists from holding on to M. However, the circulating M’s will not be able to find a sufficient quantity of capital goods on the market to create a rate of economic growth adequate to prevent the rise in the rate of unemployment. Instead of commodities accumulating in warehouses unsold, there will be inflation, combined with economic stagnation and rising unemployment.

If capitalism is to be maintained, the crisis of increasing unemployment will persist until there is a significant rise in the rate of surplus value. This increase must be enough to boost the rate of profit enough to enable a recovery in capitalist investment great enough to lower unemployment levels. In physical terms, an escalating rate of profit leads to heightened production of capital goods and auxiliary materials, facilitating an expansion of production sufficient to reduce the unemployment rate. In the manner of the neo-Ricardians, Shaikh measures “real profit” in terms of the quantity of capital goods, raw materials, and auxiliary materials. (7)

The only way out of the crisis on a capitalist basis is to reduce the relative percentage of commodities produced for working-class consumption and increase the quantity of commodities used to expand the existing scale of production. Just like the neoclassical, Keynesian, and Austrian economists, Shaikh believes the only way to reduce a stubbornly high unemployment level under capitalism is to lower the workers’ real wages. Unlike Keynesian economists, but like traditional neoclassical and Austrian economists, Shaikh believes it is futile to get out of a protracted period of high unemployment by stimulating effective demand. This leaves Shaikh, like other followers of Grossman, open to the charge that his arguments echo the arguments of the capitalists and their hired-gun economists. Shaikh’s economics will never be popular among labor unionists.

However, unlike the neoclassical and Austrian economists, Shaikh believes that capitalism should be replaced by socialism. Assuming that capitalism is retained, Shaikh offers no alternative to wage-cutting, directly or through inflation, as a way out of the crisis. For this reason, Shaikh’s (and Grossman’s) economics do not mix well with popular front politics. Shaikh’s answer, just like other members of the “Grossman school,” is that he is not interested in seeking popularity but in explaining how capitalism works and must work.

According to Shaikh’s view, during a crisis, rising unemployment will increase the rate of surplus value as conditions in the labor market shift more and more in favor of the capitalists. (8)

The crisis will continue to raise the rate of surplus value until profitability is sufficiently restored to allow investment to recover, ending the crisis. However, if the capitalist state intervenes to lower wages by attacking labor rights, as happened in extreme form under Adolf Hitler in Germany or more moderate forms under Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, the arrival of economic recovery will be accelerated. If, however, the workers successfully resist this increase in the rate of exploitation but do not initiate a socialist revolution, the crisis will continue until the resistance of the workers is broken one way or another.

Once the crisis ends, the demand for labor rises, and unemployment falls. Shaikh does not believe that actual “full employment” is possible under the capitalist system, especially on a global scale. A lower unemployment rate improves the working class’s position and thus tends to stabilize the rate of surplus value.

However, since competition among the capitalists ensures the organic composition will keep increasing, it’s only a matter of time before the falling rate of profit brings on a new crisis. Shaikh assumes it takes about 25 years to move from the end of one crisis to the beginning of the next. He does not mean “overproduction crises” that he believes can be dealt with by Keynesian methods with the help of modern non-commodity money. Instead, Shaikh means the profound crises marked by an insufficient production of surplus value that he identifies with the downturn of the “long cycle,” about 25 years after the end of the preceding cycle. Therefore it is the long cycle, not Marx’s ten-year industrial cycle, which Shaikh believes is the most important cycle of capitalism.

The Role of gold in Shaikh’s long cycles

Shaikh identifies three functions of money. First, money is a medium of pricing. Second, money is a medium of circulation, including its role as a means of purchase and payment. Third, money’s role as a medium of safety.

Shaikh believes that gold has retained one monetary function under the current monetary system. That role is as a “means of safety.”

As conditions become unfavorable for the production of surplus value in sufficient quantities to support normal expanded capitalist reproduction, the capitalists increasingly hold onto money not to expand their capital but rather to preserve their capital.

In the days of commodity money, this would exert a deflationary pressure on the economy. The capitalists postpone their purchases of capital goods and labor power, the general price level would fall while unemployment rises. This was the general pattern through the 1930s. Indeed, a “long cycle” downturn is most evident in a falling general price level. In some cases, such as 1873 to 1896, it could last several decades.

But since the 1940s, there has been no sustained fall in the general price level. Instead, with brief and slight exceptions, there have been only varying rates of increases in the general price levels.

According to Shaikh, since 1940, gold – commodity money – has been replaced by non-commodity money as a medium of pricing and circulation. However, gold has retained and even extended its role as a medium of safety.

According to Shaikh’s analysis, since 1940, capitalist governments and central banks have responded to economic downturns by increasing the creation of additional non-commodity money and engaging in increased deficit spending in an attempt to boost economic growth and reduce unemployment. Such policies work well when the problem is a lack of adequate demand. However, when the problem is a lack of adequate surplus value production, increasing the quantity of non-commodity money cannot boost economic growth but instead leads to inflation. Therefore, under “modern money,” major crises are characterized not by deflation but by inflation.

In physical terms, not enough additional means of production are produced during a crisis to fully employ the new workers appearing on the labor market. Production can increase only slowly, not because the industrial capitalist cannot find customers for all the products they can produce, but rather because they cannot find a sufficient quantity of additional means of production on the market to expand production at a rate of profit adequate to prevent unemployment from rising.

Under these conditions, the creation of additional effective monetary demand made possible by increased central bank and commercial money creation and deficit spending by the central government does nothing to boost production or reduce unemployment. What it does do is to increase inflation. The more the government attempts to “stimulate” the economy by pumping up demand the worse inflation becomes.

Therefore, Shaikh imagines that under a system of non-commodity money, as soon as the rate of profit falls below a certain level due to the rising organic composition of capital, the capitalists step up their purchases of gold bullion because they expect the central bank and government to follow inflationary demand-increasing policies that will reduce the purchasing power of non-commodity money. They increase their holdings of commodity money in the form of gold bullion– which retains its monetary role as a means of safety – to protect the value of their capital.

A rising price of gold in terms of non-commodity money signals that an insufficient quantity of surplus value is being produced and that a rise in unemployment is approaching. What Shaikh calls “golden prices” – prices calculated in terms of gold bullion – are no longer rising but starting to fall. This reproduces the falling price pattern seen in previous periods of insufficient production of surplus value crises before 1940.

Attempts to slow inflation by reducing the quantity of non-commodity that the central bank is creating, then reproduce to a certain extent the piling up of unsold commodities – overproduction – that occurred before 1940. But this is a secondary effect and not the essence of major crises – downturns in the long cycle or long waves, either before 1940 or after 1940. Regardless of the nature of the monetary system, a crisis of the insufficient production of surplus value in the absence of a socialist transformation means a deteriorating situation in the labor market for the working class.

In contrast to Trotsky, Shaikh sees the shift from long periods of rapid economic growth to slower growth — and back again — as a genuine cyclical process that will continue for as long as capitalism exists.

The semi-cycles of Ernest Mandel

In addition to being a Marxist economist, Ernest Mandel was a leader of the world Trotskyist movement. From the early 1960s until he died in 1995, Mandel was the central leader of the Fourth International, which was what the world Trotskyist movement called itself.

However, it was through his role as an economist that Mandel exercised a major influence on Anwar Shaikh. In the early 1970s, Ernest Mandel published his PhD thesis “Late Capitalism.” His doctorate allowed him to become a lecturer at the Free University of Brussels, where he spent his final years.

While Mandel expressed skepticism toward Grossman’s work in his early work, he moved closer to Grossman’s views in his later years. In the late 1960s, Mandel was won to the view that capitalism experiences long cycles. He later retreated from this when it was pointed out to him that Trotsky had specifically rejected the views of Russian economist Nikolai Kondratiev that capitalism has regular cycles of about 50 years duration.

In a cyclical process, one phase of the cycle leads to the next phase of the cycle. For example, the crisis phase of a ten-year industrial cycle leads to the depression/stagnation phase. The depression/stagnation phase leads to a phase of average prosperity. Average prosperity leads to a boom, ending in a crisis that returns us to the depression/stagnation phase.